The Rise of Fentanyl and its Connection to the Opioid Crisis

April 14, 2023

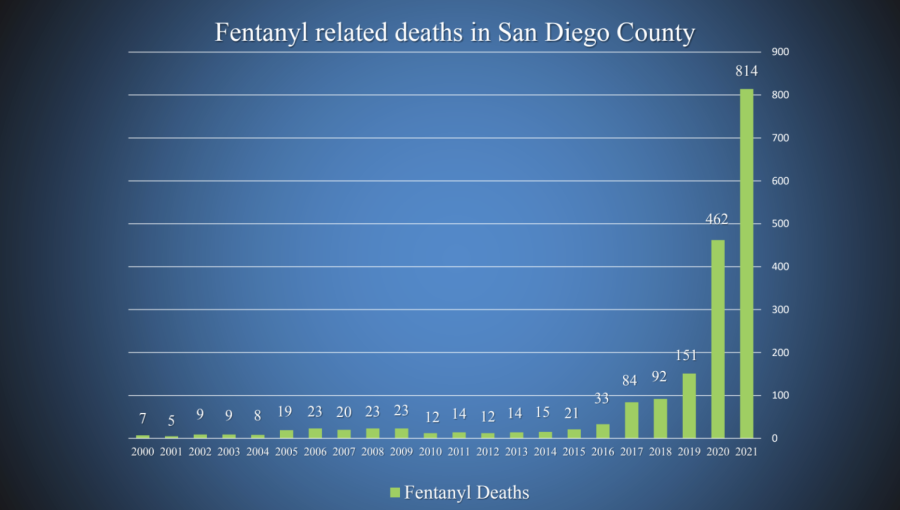

Fentanyl is a member of a large class of drugs called opioids, some of which include morphine and heroin, amongst others. Opioids are prescribed to treat pain, but some of the more powerful ones, like fentanyl, are used for anesthesia or to help with much more severe pain. However, there is a dark side to the existence of these substances. For decades, the abuse of opioids such as oxycodone, heroin and, more recently, fentanyl has been rampant, and the death tolls from overdoses are increasing all the time. None of the opioids, however, seem to share the spotlight with fentanyl.

Fentanyl’s strength, even at low doses, its deadliness (despite it being practically invisible), and its prevalence as an illicit substance, has earned its use the title “epidemic.” According to data collected from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) by the organization Families Against Fentanyl, for Americans between the ages 18 and 45, overdosing on fentanyl was the leading cause of death in 2021. By their count, the number of people who lost their lives to a fentanyl overdose was almost double that of car accidents and COVID-19 for the same year (familiesagainstfentanyl.org).

The story of the fentanyl epidemic begins in the 1990s with the onset of the opioid crisis. As detailed by Journalist Sarah DeWeert in an article published in Nature, there was a surge in the marketing of opioids by pharmaceutical companies as effective and relatively non-addictive pain relievers. The spread of OxyContin, a pill produced by Purdue Pharma, in particular marked the beginnings of this crisis. The failure of the Food and Drug Administration to detect OxyContin’s addictiveness and the lies of Purdue, which they admitted to in 2007, allowed opioids to firmly plant their roots in the United States (nature.com).

More than the other prescription opioids at the time, OxyContin had much greater potential to be abused. According to Dr. Daniel Ciccarone in an article in the National Library of Medicine, it was a new kind of pill, carefully constructed to have higher dosages that were delayed to yield a long-lasting effect. However, the delayed release could be bypassed if the pill was crushed, thus enabling the abuse of its high dosage. This abuse of prescription opioids gave way to the second wave of the crisis. As Dr. Ciccarone details in his article, this wave likely began as opioid abusers began building tolerance to the prescribed pills. Addicted, and unable to rely on OxyContin or other prescribed opioids, people turned to heroin.

According to Dr. Ciccarone, “…through the 2000s, patients admitted to treatment with heroin use disorder increasingly reported starting their opioid dependency with opioid pills.” His reasoning is that the availability of high quality and cheap heroin made the transition logical (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). In a graph created by the CDC it is shown that, between 2010 and 2016, deaths from overdosing on heroin jumped up from around one to almost five per 100,000 people.

After heroin comes the third wave of the opioid crisis: fentanyl. There are numerous possible reasons for the rise in fentanyl’s prevalence. In a congressional hearing before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations of the Committee on Energy and Commerce, Louis Milione of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) explained that the production of fentanyl can have massive profit margins. “One kilogram of pure fentanyl costs approximately in China about 3,500 dollars. If you project that kilogram of fentanyl all the way through the supply chain to the distribution level, that 3,500 dollar kilogram will potentially yield millions of dollars in revenue,” said Milone (govinfo.gov).

While heroin is produced using the extract of an opium poppy plant, fentanyl is completely chemically synthesized. The ability to synthesize fentanyl opens up the possibility for illegal manufacturers to alter its chemical structure in an effort to hide the fact that their product is essentially fentanyl. In the highly complicated criminal justice system, this can make it difficult for law enforcement to take action, since some of these altered forms, called analogs, may not be scheduled drugs that have any restrictions on them. According to Milione, “Foreign-based fentanyl manufacturers and the domestic Pied Pipers of this poison often operate with impunity because they exploit loopholes in the analogue provisions of the Controlled Substances Act and capitalize on the lengthy resource-intensive reactive process required to temporarily or permanently schedule these dangerous substances” (govinfo.gov).

Another major reason for fentanyl’s surge in use across the country is its potency. A high potency makes fentanyl much more addictive than other opioids. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the drug is highly addictive, and symptoms of withdrawal can be severe (nida.nih.gov). In an article from the health-oriented news site STAT, it is explained that, because of these severe withdrawal symptoms, addiction treatment is much harder when it comes to fentanyl (STATnews.com).

Despite how daunting this crisis may seem, things are looking up. NBC detailed the story of a Los Angeles family who lost a son to a fentanyl overdose. Their son, Tyler Shamash, had shown no signs of fentanyl in his system. The next day, he fatally overdosed on fentanyl, as shown by a coroner’s toxicology report. His mother, Juli Shamash, was astonished to learn that current urinary drug screenings didn’t even check for fentanyl. Her son’s death inspired her to propose legislation to the state, which took effect this year by adding fentanyl to the list of substances screened in urinary drug tests (nbcnews.com). Tyler’s story shows how we are unable to rely completely on existing institutions and policies to stop the opioid crisis and the fentanyl epidemic, but also that, with enough determination, it is possible to make significant progress.